On the 6 th of February 2024, a student pilot and trainer met at Gold Coastline Airport in Queensland for a twin training trip. The clear lesson discovered that day was an usual one: if the approach is not stabilised, walk around! Yet to be reasonable, the instructor did walk around, simply … a bit later than a lot of us would certainly have. But I’m prospering of myself.

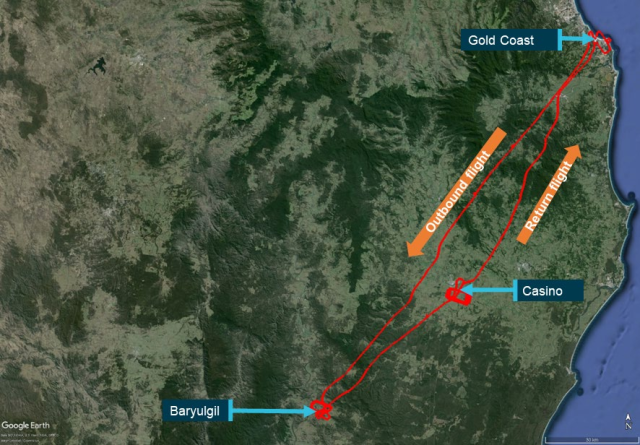

The pupil pilot and the teacher left for that day’s training in a Cessna 172 R possessed by the trip institution, signed up in Australia as VH-EWW, at concerning 11: 38 local time. The climate that day was warm: 31 ° C (88 ° F). The flight guideline was uneventful: they flew to Baryulgil where they did some aerial work. On the way back, they did 5 circuits at Gambling establishment, leaving just before 14: 00 to return to Gold Coast Flight Terminal. It seeks to me like the plan was to end up at 14: 30, producing a three-hour lesson.

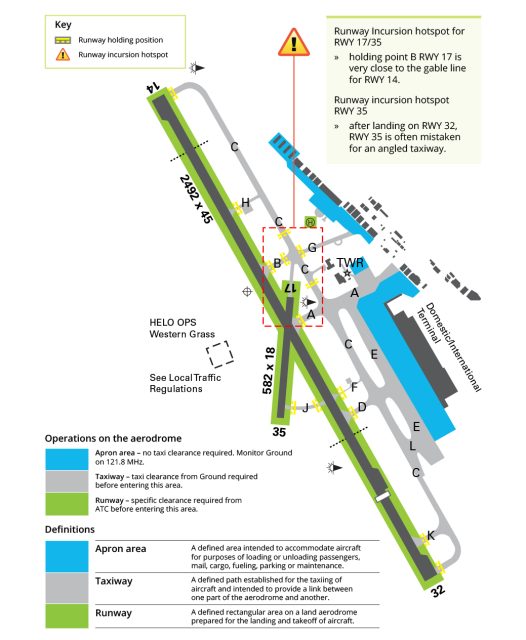

Gold Shore Flight terminal lies at the southern end of the Gold Coastline, about 90 kilometres southern of Brisbane. The airport and its 2 paths are about 21 feet over mean sea level. The primary runway, 14/ 32, was extended in March 2007 to its present size of 2, 492 metres (8, 175 feet). The second runway, 17/ 35, is just 582 metres (1, 900 feet) and converges the much longer one.

When they were about ten maritime miles southwest of the flight terminal, the student pilot called Gold Coastline Tower air traffic control to claim that they were incoming. The controller got rid of the flight to enter regulated airspace and to track direct to the flight terminal at 1, 500 feet, anticipating path 32 Not long after, they were gotten rid of to descend to 1, 000 feet. Then, they were just over 6 miles from the airport and monitoring for an appropriate base leg for runway 32, that is, signing up with the circuit at an ideal angle to the final approach and path instructions.

There was a Boeing 737 also inbound to Gold Coast Airport terminal’s runway 32 and taking a trip a fair bit quicker. The controller worried that the Cessna might be sluggish on the technique. For a light airplane such as the Cessna 172 R, the rate flown during the final method can vary by 20 to 30 knots; at greater rates, the pilot will certainly reduce right before goal for a more regular landing rate. The controller knew that student pilots typically are available in slow, which might suggest that the Boeing 737 would have to go into a holding pattern or go around while the Cessna landed.

He called the Cessna 172 R to ask if they might “accept path 35, best rate” in order to keep path 32 clear for the Boeing 737 This would certainly suggest some quick thinking to align for path 35 and get ready for landing on a much shorter runway.

The student pilot’s initial response was that they could not do it. The Cessna was too expensive and too near to the runway, currently simply 3 9 nautical miles from the path threshold. The trainee had actually only arrived on the much shorter path when in the past.

However the instructor quickly exercised, properly, that they were in a perfectly excellent placement to method path 35 The wind was coming from 010 ⁰ at 15 knots. For path 35, that indicated that they had a headwind component of 14 knots and a crosswind of 5 knots. This would certainly be a great chance, the instructor idea, for the pupil to exercise landing on a much shorter runway.

The instructor responded to the controller: “Affirm.” Yes, they would certainly approve the controller’s request. The controller cleared them for a straight-in technique to path 35 at best rate.

Their rate still mattered since path 35 crosses path 32; the controller required the Cessna to land and be free from the runway prior to the Boeing 737 can be cleared to arrive on path 32

As the Cessna reached 2 miles from the threshold of runway 35, the controller removed the Cessna for an aesthetic technique, stating, “I require best rate all the way in to going across the path.”

The instructor had gotten instructions before for “ideal speed” yet never “to the path”. Still, he believed they can comply.

The initial thing they required to do was to reduce their airspeed to set up the airplane for landing, so the trainer informed the student to minimize the throttle to idle while lowering the airplane’s nose to maintain best speed. The airspeed lowered to under 110 knots. The student extended the flaps to 10 °.

On a typical strategy, the pilot remains to expand the flaps as the airspeed minimizes, to make sure that the flaps are totally encompassed 30 ° for the landing. In order to safeguard the structural stability, the airplane needs to be travelling below 85 knots for the pilot to remain to safely prolong the flaps for touchdown.

Yet as the instructor wished to guarantee that they kept “finest speed” for the approach, they proceeded at 90 knots and did not expand the flaps additionally. The Cessna proceeded at 90 knots or greater for the remainder of the approach with the flaps left at 10 °. To maintain the speed up, they approached considerably, at 5 ° instead of a secured method profile of around 3 °.

The benefit of having the flaps totally prolonged is the rise in drag, which slows down the airplane and permits a steeper descent on strategy and a lower goal speed.

The typical touchdown distance for the Cessna 172 R with flaps totally extended is about 400 – 430 metres (1, 300 – 1, 400 feet). This meant that they were great landing complete flaps with the 582 metres on runway 35, particularly with a 14 -knot headwind.

A landing with the flaps only partially prolonged is not inherently dangerous; pilots often choose to land with 10 ° flaps, for instance in crosswind conditions. Landing without the flaps completely extended requires more stopping range.

If they were landing on runway 32, as originally prepared, 2, 492 metres was sufficient runway to safely land and reduce, even if they used no flaps at all. Prolonging the flaps to the first quit of 10 ° still permitted lots of stopping range for them to touchdown at a faster rate.

Nevertheless, the reality remains that a lower goal rate and less stopping distance are significantly considered favorable characteristics for a short-field landing. Technically, a good pilot can land a Cessna in 177 metres, although more realistically in 408 metres, needed for a less superficial method to ensure that they would certainly get rid of any barriers up to 50 foot in their approach path. With the 14 -knot headwind, the touchdown distance needed dropped to 368 metres. Even an average pupil pilot at the end of a lengthy day need to be able to arrive on runway 35 in these situations.

Yet 368 metres is presuming the airplane is established for a short-field touchdown: flaps completely expanded at 30 °, crossing the threshold at 62 knots with the power totally idle, with optimum braking on a completely dry path).

Trying to land at ideal rate with 10 ° flaps on runway 35 might have been possible for an experienced pilot, particularly if there were no barriers on the strategy. However it certainly left no margin for mistake.

At one mile out, the Cessna was coming down via 500 feet at 95 knots ground rate. The controller removed the flight to land and advised them to continue to taxi into GOLF, describing the taxiway at the end of runway 35, soon after the crossways of path 32 and the identical taxiway CHARLIE. The telephone call confirmed that they were removed to go across the path 32 junction. Once they were securely out of the way on taxiway GOLF, the Boeing 737 can land without issue.

Yet at the very same time, the controller realised that they were approaching much faster than typical. It didn’t occur to the controller that they were attempting to preserve “ideal rate”. Instead, the controller presumed that the Cessna had actually decided to abort the landing on path 35 and simply hadn’t made the telephone call yet. Probably with a small sigh, the controller began a plan to re-sequence the Cessna for a walk around.

The typical landing speed for the Cessna 172 R is 61 knots with flaps totally expanded or 66 knots with the flaps withdrawed. The FAA specify a secured technique to be a constant-angle glide course within + 10 and – 5 knots of the suggested touchdown speed. If the method is not secured or ends up being unstabilised under 300 feet, the pilot needs to quickly launch a walk around.

The Cessna was travelling at 90 knots with only 10 ° of flaps to a path with little room for mercy. A choice to terminate the touchdown and walk around for a second effort once the Boeing was out of the method would certainly have been a great strategy.

However, as this was a willful decision to abide by the guideline to keep best speed “right to crossing the runway”, the guideline really did not think about the approach to be unstabilised and mored than happy to continue.

The pupil pilot remained to approach. They went across over the threshold of runway 35 at 100 feet and 90 knots showed airspeed (regarding 80 knots ground speed): fast and high.

The Cessna drifted in ground effect just above the runway, which would have really felt to the pupil like they were on the pillow of air. Lastly, the wheels touched the path, but only briefly. The airplane bounced back right into the air.

The trainer attempted to guarantee the student, claiming to continue the landing rather than go-around.

This kind of light bounce is easily recoverable if you have enough runway. I as soon as delicately bounced a Cessna 152 on Malaga’s path 3 times and still had a couple of thousand feet in which to brake and shut off the path. Yet the trick here is “enough path”.

The instructor, having lost some level of situational awareness, urged the student to continue as there was a lot of path on 32 to recuperate the landing.

However they weren’t on path 32 There was not lots of path left on path 35

Once more, walking around at this point would certainly have been an excellent plan: after the bounce, the trainee pilot ought to have used complete power, complied with by gently drawing back on the controls for a slow-moving climb away.

Rather, the teacher had decided they must proceed.

The Cessna touched down once again, this time securely. They really did not have much runway left. The trainee used complete brakes.

Remember what I said regarding no margin for error?

The high speed landing and abrupt stopping triggered the wheels to lock up. The Cessna’s momentum kept it competing onward along the path, the tyres skidding as opposed to rolling.

The teacher took control and drew the control column back, intending to increase the weight on the wheels and regain control of the steering. The Cessna proceeded along the runway at broadband. They raced with the path 32 intersection.

The controller, viewing from the tower, called “Show up [taxiway] CHARLIE if need be.” It would certainly be much easier to turn left onto CHARLIE which would certainly provide them a long and straight run, alongside path 32, in which they could reduce the airplane.

The teacher listened to the controller’s phone call but couldn’t refine the direction promptly sufficient, already concentrated on making the sharp right turn onto taxiway GOLF.

As the instructor turned, the Cessna skidded left of the taxiway onto the yard, barrelling towards a water drainage ditch.

It was since the teacher chose that of course, perhaps they ought to go around.

This was likely an instinctive response as they bumped over the yard with the drain ditch noticeable before them. The trainer used complete power and drew back on the control column.

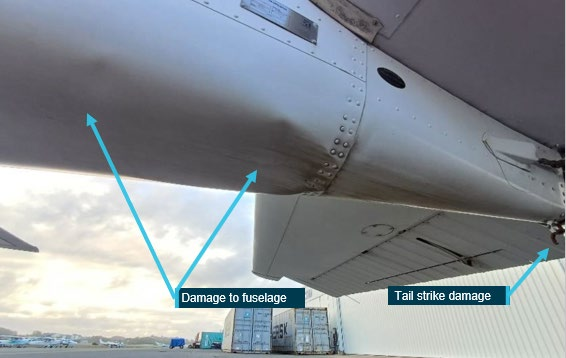

As the nose increased in feedback, the back of the aircraft struck the ground.

Seeing aghast from the tower, the Boeing 737 most likely forgotten, the controller turned on the collision alarm. This instantly states an emergency situation and notifies emergency services.

The instructor continued complete power. The airplane gradually climbed away, missing the drain ditch. Now they were flying unsteadily in the direction of a row of hangars.

Inside the cabin, the stall warning horn sounded. The Cessna 172 R’s delay alerting audios in between 5 and 10 knots over the stall. Currently at complete power, their options were restricted. Yet levelling bent on raise the speed implied flying directly towards the hangars.

The trainer reduced the nose a little and aimed for the lowest roofing, really hoping that they would remove it. The telephone call to the controller seems unreasonably tranquil: “Just had to make an emergency walk around.”

There’s no reference of the pupil pilot but if it were me, I can tell you that my eyes would certainly have been firmly shut.

The Cessna removed the hangars and continued to climb.

The controller passed the airplane to an additional controller; the record does not discuss why, yet I think it was for a quick change of trousers. The new controller notified the teacher that they had actually experienced a tail strike and asked whether they thought they can conduct a normal approach and landing. This is an entirely reasonable inquiry: is your airplane flying normally? Can we series you in or do you require emergency actions? But you’ll forgive me for envisioning that the tone of voice for the inquiry indicated “as opposed to whatever the heck that simply was …”

The teacher confirmed that, yes, they could. Now that they were free from the garages, there didn’t appear to be any pushing troubles or problems as an outcome of their tumbling over the turf and striking the ground.

The trainer remained in control, entering an appropriate circuit and circling once on downwind at the controller’s demand, in order to enable better spacing with various other airplane.

The Cessna arrived on runway 32, the longer path, safely at 14: 34, regarding 10 minutes considering that the initial decision to land at “best rate” on path 35

I’ve put best rate in quotes since, although this is an usual demand from controllers, it’s not in fact clearly specified and is not provided as a conventional phrase in the Airservices Australia AIP (Aeronautical Information Magazine). Obviously, controllers should do not hesitate to make use of the phrases that match the moment, aiming for clear and succinct plain language. And the fact is that every pilot understands that the point of ideal speed is that the controller desires you off the beaten track as promptly as possible.

In this case, the controller believed that if the Cessna carried out a regular method, they possibly would not have had time to land before the incoming Boeing 737, especially as training aircraft in some cases flew really slow approaches.

It was sensible for the controller to ask the Cessna pilots if they might keep their speed up so that they would have landed and cleared the path prior to the incoming Boeing 737 would get on last approach.

What the controller expected was for the Cessna pilots to maintain their speed up for a lot of the method however then lower their rate to typical technique speed quickly prior to the threshold.

The factor of “ideal speed” is that the pilot needs to decide what is the most effective rate that they can achieve to continue the strategy and land securely. What speed is secure can differ based on the aircraft, the situations and the experience of the pilot. A secured approach can be as much as 10 knots above landing rate, so a reasonable analysis would certainly be to keep at least that speed, in this instance 71 – 76 knots, up until the last minute of the technique.

It would certainly additionally have been flawlessly sensible for either pilot to claim that they could not conform, for whatever reason. The controller after that would have needed to make a decision: ask the Cessna to abort the touchdown and walk around to make room for the Boeing 737, or allow the Cessna to proceed, taking the danger that the Boeing 737 would certainly have to go about because the path was not clear in time.

In this situation, the trainer mored than happy with the path adjustment and preserving best rate. The instructor wished to help the controller by getting in quickly, to ensure that the Boeing 737 was not hampered. This was concurred with the flight at 1, 000 feet and regarding 1 9 nautical miles from the flight terminal. There had not been a lot of time to think about it.

The trouble was made worse by the phrasing of “best rate across the runway

The record does not get into this, but I assume that the controller was talking about rolling throughout path 32 after touchdown. That is, I would have taken the controller’s declaration to suggest “please fly a high-speed strategy and land normally, once you have touched down, please do not slow needlessly up until you have gone across the intersection of path 32”

To be fair, the Cessna certainly did go across the intersection extremely promptly.

After the occurrence, the trainer stated that it was necessary to be a lot more assertive in future and tell air traffic control that they might not comply with preserving finest speed while performing a regular technique.

This strikes me as being the wrong lesson. Preserving finest rate for the strategy, that is, proceeding at 90 – 95 knots and flaps at 10 °, would have been great if they were landing on the longer runway. However even having accepted come down on path 35, proceeding at 90 – 95 for the method and slowing down to 66 knots for the touchdown was still a practical choice, as was further prolonging the flaps in the last minutes of the technique.

Another option would certainly have been for the instructor to accept ideal rate and afterwards be prepared to take control soon before touchdown. Or, becoming aware that they were going across the threshold at 100 feet over the path and travelling 25 knots above touchdown speed, the teacher can have advised the pupil pilot to walk around.

When the Cessna jumped right into the air, the trainer forgot which runway they got on. The instruction to continue was a severe error, as it was no longer feasible to securely land the airplane; the guideline to proceed was categorically incorrect.

My factor here is that the failing was not that the instructor conformed as opposed to refusing. The instructor eroded their safety margins with every acceptance, leaving the pupil pilot to attempt a quick landing on a brief runway under demanding conditions at the end of a long lesson. The genuine error was the trainer repeatedly making a decision not to break short and walk around, regardless of the method and landing being plainly beyond reasonable limitations.

The AAIB’s final report concludes with the complying with adding elements:

- The air web traffic controller’s demand to keep best rate to the runway, combined with the teacher’s interpretation of the guideline, caused an excessively rapid approach.

(again, quick sufficient that the controller, that had requested ideal speed, assumed that they were terminating their strategy to walk around and just hadn’t called their intents yet.)

- Although the aircraft went beyond the speed for a stabilised method, the teacher did not carry out a go-around prior to touchdown or while on the runway.

- The too much landing speed caused decreased stopping performance and a loss of control during the turn onto the taxiway.

- Complying with the loss of control, a go-around was started to prevent a drain ditch, resulting in a ground strike and near collision with garages found on the eastern limit of the flight terminal.

As an outcome of this crash, the trip school has examined their treatments for stabilised and unstable methods and examined the training product for trainers and pupils, including interaction, choice production and assertiveness. The trip institution likewise launched conversations with the trainers about the training obstacles at Gold Coastline Flight Terminal and how to manage non-standard ATC demands and clearances, consisting of refusing clearances.

I have a lot of concerns outside of the remit of the final record, as an example: what took place to the pupil pilot? There’s no reference of whether the pupil proceeded with flight lessons. I hope so, yet with a various trainer.